- Home

- Aida Edemariam

The Wife's Tale Page 8

The Wife's Tale Read online

Page 8

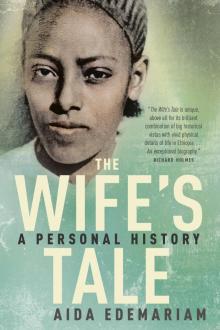

Come, he said, another time. Come where? She had had her hair braided, had bathed and put on her best clothes, but that was because she loved the feel of cleanliness, the smell and softness of fresh-washed cotton, not because she expected to go anywhere. She had wound Yohannes in another length of clean white muslin and tied him to her back, where her breath and beating heart had carried him into sleep. Come. Let’s have a picture of you. She laughed, disbelieving. It’s true. There’s a photographer at a house down the road. Let’s go.

The photographer was an Italian. Her husband looked back and forth between the foreigner, who fussed and tweaked and clicked, and his wife, who sat straight and still. In the photograph her skin is clear and youthful, tight over a long, perfect jawline, but she seems older than twenty-two or twenty-three. Her eyes look out as if from a place of safety somewhere behind her head. A suggestion of a frown shades the inner edge of each brow. For the rest of her life she would look at this photograph and think, if I had known what would happen, if I had been more sophisticated, I would have held my son in my arms, and we would have faced the camera together. But it did not occur to her, and after the Italian had finished her husband took her home.

But mostly she worked. She fed all the Ethiopian labourers – fed the hewers of wood and the hewers of stone and the carpenters and the masons who joined what they had hewn together: fifteen people, sometimes twenty, including one strong man who could eat three injera at a sitting. Fed the four servants who helped her, fed her family. Fed any guests her husband saw fit to bring home. Fed any relatives who walked in from the countryside or across the city and sat in the receiving room, silent or relaying news, pausing to rise and bow whenever she or her husband entered. Fed them roasted grain and dark beer at lunchtime, and then a full supper in the evening, when she stood and circled and watched and made sure everyone ate as much as they were able. The servants cleaned and ground grain, picked through raw spices, drew water, but it was she who baked huge piles of injera every day, and cooked the sauces, who boiled coffee and sat on a low stool pouring it. It was obvious to her that her husband had no idea how much labour he was creating when he brought yet another man home and said, he’s been working, let him eat, no idea even though he saw that she rose at five every morning and did not untie the thick girdle that supported her back and held up her growing belly until after eleven at night. Carefully she would sit down onto the hide bed and ease herself flat, listening to the finally quiet house, thinking, this church is killing me.

* * *

—

So now she looked at the woman in front of her, knew, from her tone, this was no routine visit, and fear licked through her like flame. What is it?

‘He is in danger. You are both in danger. A gun has been hidden in the church, in the vault below the holy of holies. They know about it. They are coming to search your house. They are coming now. Don’t be scared. There is no time to be scared. We must search everything before they come, to make sure nothing has been hidden here as well.’

And so they began. Under the seats in the receiving room, under the hollow bases of the mesobs, Edemariam, who thought it all a good game, toddling busily about behind them. Through the clay pots and sacks in the hut where the servants ground grain. In the rafters. Behind the piles of cooking pots in the kitchen hut, inside them, under them, while a Maundy Thursday porridge of wheat flour and split broad beans plopped over the fire. In the storehouse on the ground floor of the main building they sifted through the madigas of teff, of dry peas, of lentils. They plunged their arms into the mess of fermenting red wheat waiting to be made into beer for Easter Sunday. They swirled their hands through the dregs of previous beer-makings, and through the water pots. She felt behind the clothes hanging on hooks in the bedroom, rifled through all the sheets, under the children’s blankets, under the servants’, into every possible cranny. Nothing. Then she remembered their own gun in the thatch, and shoved it deeper, as deep as she could reach.

‘Good,’ said the informer, and took her leave.

And, just as quickly, it seemed, was back, alongside the carabiniere.

How handsome he was! Shining black boots. Belt fastened tight. Buttons like new thalers. Gun held just so. She could feel herself shaking, praying it wouldn’t show.

She could hardly bear to watch as he followed their trail around the house. After a while she became aware of a movement in the corner of her eye. She glanced at her son. He was reaching for the ceiling, pointing up to the thatch. She snatched him up, pulled in the fat arm. He wriggled free, and reached again. She held him more firmly, and he fought her, squalling.

She glanced at the carabiniere. Had he noticed? But he was dragging his hands through the grains, peering behind the large clay amphorae. Rolling up a sleeve and plunging an entire arm into a gan full of pea-water and dregs, where he paused so long her heart skittered with panic. Had he found something? What had they missed? Her shaking intensified till she thought she might fall. But his hand came up empty. He shook the water off, fastidious, and finally, finally, he and the informer left.

* * *

—

It was late on the day of the Crucifixion when her husband returned, and she washed his feet and put food in front of him, and waited, bowed, till he had eaten before she told him.

Master. Her voice like someone else’s. Someone has planted a gun in the church so the foreigners think it is yours and kill you. You must disappear. Go, now, to Gonderoch Mariam, and the Qimant will escort you to Metemma. There are patriots there, fighting for Hailè Selassie. Join them.

No.

Go. I will stay here, with the children. They won’t touch me, and if they do, it’s God’s will. Go now.

No.

They will kill you. I cannot watch you die.

I will not go.

Have you not spent these last years watching your colleagues die? Have you forgotten the priests executed in front of you while you prayed for their souls, fasted for them, grieved for them? Would you have the same done unto you? I beg you, go.

The Mother of God hasn’t abandoned me yet. I will not leave.

* * *

—

When darkness fell that Good Friday he wrapped himself in his cape and gabi and stepped out through the gateway. It was mid-morning on Saturday when he returned.

He’s dead.

Who?

The man. The man who planted the gun.

What?

All night, he said to her, while around him his priests and deacons chanted out their books of hours, as they read from the Old Testament and from the New, as they recited the Miracles of Mary, he had prayed, standing, kneeling, bowing until his forehead touched the rough ground. Oh my mother, please do not let me die for something I have not done. Oh my mother, I beg of you, keep me safe.

After the dawn and the service of peace, after the priests had blessed and handed rushes to each worshipper to tie about their foreheads in memory of the grass the dove brought to Noah, he had made his way slowly out of the little church, past the junipers and olive trees, the drunkenly leaning gravestones. Slowly he became aware of a woman weaving among them, a young slip of a woman like his wife, keening for someone dead. He recognised her.

Who died?

My brother, came the answer. He was found in his bed last night. No gunshot wounds, no evidence of poison. Just dead.

In the house near the market he looked at his wife. Yetemegnu. The Mother of God killed him for me. He tried to kill me, but she heard my prayer.

And he had gone straight back into the church and bowed and bowed again, praying his thanks.

Now she watched as he took a cape embroidered with gold and drew it over his shoulders, as he wrapped a silk turban around his head. She watched as he picked up his prayer stick and fly-whisk and left for the Piassa and the castles, where all the priests and deacons from all the forty-four churches of Gondar, and the rural churches of Begemdir and Semien – though now it was called Amhara – all

the men the Italians had asked him to bring, milled about the walls. They carried heavy gold crosses and swung gold censers; they sheltered under umbrellas of red and green and blue silk, they held aloft yellow wax tapers. Their capes blazed with golden suns. So many standing under the sycamore fig the earth was hidden, they told her, as far as the eye could see.

The foreigners were there too, in their finery. Man after man from both sides climbed up to the balconies of Empress Mintiwab’s palace and addressed the crowds, vying to outdo each other in panegyric ardour, priests buying favour for favour’s sake, pomp and position being pomp and position and particularly material gain whatever its provenance, but watching also for emollient effect, aware always – had they not had plenty of practice, under emperor after warlord after emperor? – that present flattery bought precious things: fragile safety, time, space. Space in which to decide whether and when and how to act, and thus to wrest fragments of freedom and power from a time in which both were in short supply. And so they called out to their flocks, Look! Look what the Italian has done for Ethiopia and Ethiopia’s church. Look how the Italian respects our great religion, and increases the power of our faith.

But the Italians had their ruses too, one of which was a belated decision not to allow themselves to be used as instruments for the settling of private scores. And so one of the highest ranking among them beckoned to Aleqa Tsega. ‘Come here,’ he said, to the slight dark administrator of all these hundreds of men. And, as she heard it later, he reached forward and clasped her husband’s hands. ‘I know what happened this morning, how you were saved. You must be a very holy man.’ And he raised his voice and addressed the crowd. ‘From now on I will hear nothing, no rumours, no spies, nothing against Aleqa Tsega. I will believe no ill of him.’

So when the cock crowed before dawn on Easter morning and the long hard fast was broken with crushed flaxseed and honey and drumbeats and ululation, when the sheep’s blood ran in rivulets and reddened the green grass in the yard, when the gans of barley beer and honey wine were poured out and when their guests, flushed and loud with holiday plenty, sang her their poems of praise – Oh brewer of mead, Oh brewer of mead, wash your hands in honey – when even on the second day the priests faced each other in rows and shook their sistra and danced, there was an extra freight to their celebration.

* * *

—

She had never been able to face food when she was tired, and now the exhaustion of the work was exacerbated by a pregnancy that made her so sick she could not eat even if she had tried. Her cheekbones clawed out of her face. Her arms and legs were knob-bled sticks. She grew so thin the large belly she carried before her began to look obscene, added on.

Her husband watched with concern, knowing from her previous lyings-in how specific her requirements would be when she finally gave birth, how the rough sauces of the well-meaning village women would go untouched. So he took some fresh beef, cut it into even strips, and hung it on twine strung across one of the storerooms. When it had curled and dried into a dark red jerky he took it down and placed it in a leather bag, ready for when she needed it.

It’s for my child, he said. It’s for my child, for when she gives birth.

The labour this time was fine, though after the last one almost anything would have seemed so. She named the boy Teklé-mariam, plant of Mary, and a gelded sheep was slaughtered, but the message had not got out and there were few guests. Her husband called a neighbour to him and handed her the leather bag. Take this. Break it up in a mortar and cook it with spices and butter and pieces of injera, just as she likes it.

When it was ready he brought it steaming in to her. Slowly, trying not to disturb the baby in her arms, she sat up and took a grateful mouthful.

* * *

—

Meetings, then, meetings and more meetings. All the necessary meetings of an aleqa and a liqè-kahinat – the questions, the applications, the letters to dictate, the promotions and demotions, the importunings and the blandishments, the straggle of petitioners anyone with any power at all carried with them in their daily round. And he, as administrator of forty-four churches, had plenty of power. But even to her, to whom he told nothing, it was obvious the number of meetings was increasing.

Meetings, meetings, meetings, so his movements became entirely unpredictable, and she instantly regretted the one instance she took advantage of an absence to leave the house. She had been preparing shirro, dried peas and chickpeas pounded fine with cardamom, fenugreek and rue, when she realised she had no sieve. She rocked the new baby to sleep, picked up her skirts and ran to the neighbour’s. She didn’t go in, but stood at the doorway, asked for the sieve, ran back. She had hardly entered her home when she heard a thud next to her shoulder. She turned. A machete was embedded in the door; the thick wood had split, above and below the blade.

She had given her husband one wide look and left as fast as she had come. And the elders had been furious with him. What if you had killed her? What in God’s name were you thinking? What has this child ever done to you? That time she had stayed with her relatives for weeks.

Meetings in the refurbished castle of Empress Mintiwab, with the Italian governor and his deputies, in which, standing in front of a fellow priest about to be hanged, he argued that if they must punish to punish fairly; that if unfair sentences such as this went ahead, all of his priests would remain in the public square, in protest. The priest lived.

Meetings with his foreman, meetings with masons, meetings with the two painters he had imported from Gojjam, who were covering the walls with faces, with robes of blue and red and green and gold: Pious Gelawdewos, defeating Ahmed the Left-Handed at Zantera in Infiraz and saving the Ethiopian empire for Christianity; St George forever slaying his dragon; Satan horned and bound in flames; Mary and her son, guarded by archangels.

More meetings in the wide space outside the castle walls, huge meetings, where the Italians indulged their taste for mass rallies, for appropriated imperial pomp and for grandstanding speeches, where the priests responded in kind, and everyone watched everyone else like vultures. ‘I will keep my mouth,’ said her husband, walking down the massed ranks of his priests and deacons, speaking low and urgent, quoting the psalm in the old language only they could speak. ‘I will keep my mouth.’ None of them would be here unless they had learned the rest of it by heart: ‘I said, I will take heed to my ways, that I sin not with my tongue: I will keep my mouth with a bridle, while the wicked is before me. I was dumb with silence, I held my peace, even from good; and my sorrow was stirred.’

Big meetings, disguised as parties, for as his church grew, so did the circle he made for its influence. The clergy were used to celebrating the yearly feast of Ba’ata with handfuls of roasted grain and a horn or two of dark beer. But on the third day of the fourth month, when the heavy rains were a memory and the lush green of the valleys was giving way to brown, he sent invitations not just to the usual clerics, but to other dignitaries too: church administrators, the headmen of outlying villages, the old warrior Ayalew Birru. Aged Abunè Abraham. Come, Tsega said to them all, help me to celebrate Her Presentation and Entry into the Tabernacle. Come to my house, there is food waiting. They arrived by the dozen to eat the fasting stews she had prepared, and he walked among them, making sure no one went hungry, that the servants kept the drinking horns full to slopping over. Each year the feast continued for longer, guests arriving not just on the third of the month, but for days after.

Small meetings, to which she was also witness, with their family confessor and his son, who slipped in after dark and wrote letter after letter for a husband who paced in and out of the trembling pool of lamplight, dictating their contents because his father’s curse still held and he was not allowed to write.

Meetings, and more travel, setting off among groups of convivial, bowing, chronically suspicious clergy, leaving at dawn in a clatter of mule hooves and clanking bridles, the deacons half-walking, half-running alongside, Tsega inward-facing a

nd stern under his large white turban, the letters his confessor had written tucked deep into his clothing. Official meetings with churchmen, with elders, but also, afterwards and in secret, with sharp-eyed men hung with belts of bullets, whose hair had been left to grow long and matted and stuck out from their heads like lumpy thatch, who listened to his reports of Italian movements, took the proffered papers, read them, then buried them in their own clothing, ready to be passed on. Meetings at churches across the wide province, licensed by his job, by his aleqa-ship of Gonderoch Mariam, by the Italians, to range free through valleys and mountain passes steadily slipping out of their grasp.

Meetings of which she knew so little that when one of his trips extended into weeks she panicked, believing the Italians had taken him, as they had taken so many others, to ‘Rome’, and she would never see him again. She wept until her neighbours said, Yetemegnu, you must stop. You are watched, we are all watched. The Italians will hear of it. But she could not stop. So they said, go. Take your children into the countryside and go. And she lifted Teklé onto her back, and they all walked up the mountain to Gonderoch Mariam.

After a month he returned. Abunè Abraham had died, and the prior of Debrè Libanos had been promoted into his place; the Italians had indeed flown her husband north – but to Asmara, to participate with colleagues from the other provinces in the choosing of a phalanx of new bishops. On the way back he had visited the holy city of Aksum and used some of the money the Italians had given him to buy a high rich curtain for Ba’ata’s holy of holies. The party to welcome him back lasted days.

The Wife's Tale

The Wife's Tale