- Home

- Aida Edemariam

The Wife's Tale Page 12

The Wife's Tale Read online

Page 12

So whatever came to her she sent smartly back. But sometimes she felt irritated. Everyone else took these inducements; they were so common in the courts they were almost considered fees – why did he have to be the only one who refused? Once a priest she knew slightly came and sat in her reception room and fished out from among his robes a thaler’s worth of the best coffee. ‘I know you love this; it’s fresh from Jimma. Let’s drink it together when I come to visit.’ She refused, and he left, but came often after that, to sit, and chat, and eventually – what harm could it do? – she accepted enough beans to make a glorious pot of coffee.

What does the priest want? she asked her husband one day. Can’t you finish your business with him, and send him away? He looked at her. Why do you care? You don’t normally ask these things. I’m just curious. Did you take a bribe? Swear you didn’t. But she could not swear, and finally, fearfully, she answered, he begged me to take coffee with him. I will never do it again.

Her husband laughed. But this is how bribes work – don’t you see? They inveigle their way into your kindness – never do it again. And again, she promised.

* * *

—

In the afternoon she sat in the shade in the back yard. The sky was high and deep and blue, and the hills were parched. The birds were silent in the junipers and a breeze tickled the leaves of the young eucalyptus trees, making them shiver in the sunlight. They were coming on well – it had not been long since they planted them, he scooping a hole out of the ground, she following with the seeds, placing them exactly, covering them over. They would never need to buy wood now, for fire or for scaffolding.

The basket of barley on her lap had a comforting heft. She combed through the grain with her fingers, picking out crumbs of red earth, errant stalks, husks dry and light as ladybird wings. Every so often she took a few handfuls and spilled them into a smaller, flat basket, then shook it from side to side until the barley lay a kernel deep. A snap of her wrists and the barley described a parabola, twisting through the afternoon, perfect but for the faint fuzz of dust sloughing off into the air.

She soaked the kernels overnight, drained them, shut them up tight in a covered barrel. After three days they began to germinate, white roots clawing out and tangling with their neighbours’. She enlisted the help of anyone available, and together they lifted up the mass of growing matter and spread it out on wide false banana leaves on the ground. She covered it over with more leaves, and then with stones, flattening the sprouts into a wide malt cake.

There was so much that when she reached up to store it in the kitchen rafters for the rainy season, it formed a second roof.

* * *

—

She said to him, in passing almost, because she thought she knew the answer, my brothers are marrying, two of them. I would like to be there to see. You must go, he answered. Take Alemitu with you. He borrowed a mule for her, and she and her daughter rode through ripe barley fields to Atakilt Giorgis, where two oxen had been slaughtered, and a sheep, and the barley beer and honey wine flowed for four days. On the third day, she stood and made her way toward a circle of clapping, dancing women. For a long moment she watched, then moved forward, and the women, feeling her approach, parted to make a space for her. Hands on hips. Shoulders down. Body steady. Pause. Jab, with her chin, forward. Jab, to the side. Forward. The other side. Faster, faster, the rest of her body motionless. The circle reformed, recognising her gift and placing her at its centre. She danced until her face broke open with laughing. She danced until she could barely move. A brilliant wedding, everyone said afterwards. Such a brilliant wedding. A brilliant wedding, she replied.

When she returned she began to test, little by little, the circumference of her liberties. She shopped in the market. She redraped her shemma so it covered her shoulders and her hair, and she went to Ba’ata, bowing at the entrance, kissing the outer walls, walking home again. She took communion, and later she took her children to communion also, tying the smallest onto her back with a broad shawl, letting the others follow her through the streets at their various speeds.

She began to go more often, each Sunday if she could, and if he was away, during the week as well. She craved the moment when she could step through the rough gate and into the church compound. Birds chirred, roosters crowed, and if there was a service in progress, a drum thumped the de-dum de-dum of a heartbeat from the holy of holies. In the wet season the rain dripped from the jacarandas and the faithful shivered under the eaves; in the dry season they searched out the shade. Outside the bethlehem nuns picked through wheat, and the occasional gelada baboon bounded through the tops of the fern pines.

To the south doorway: lips and brow, lips and brow, against the rough stone, then, discarding her shoes, into the sweet-smelling dusk of the church. As her eyes adjusted she would turn toward her favourite spot, under Mary robed in blue and red and gold, eyes large, face pale and shadowless, holding her grown son. The Virgin was guarded by angels and surrounded by more frescoes which, because Yetemegnu could not read, were in effect her Bible. She would sink onto her knees. Her mind, busy with chores and children, would begin to follow the chants, the drum, and to still. Her stomach would growl, and she would feel a kind of satisfaction at this reminder she had fasted the requisite eighteen hours, had asked forgiveness of anyone she thought she might have wronged, had kept herself away from her husband, had worn her very cleanest clothes. A kind of peace crept through her.

The sun would be high by the time she left the church. Everyone she passed bowed, How are you? Are you well? Your husband? Your children? Your cattle? All well? and she would bow back, murmuring, Well, thanks be to God. All well. And you, are you well? When in the final decades of her life she found herself living far from home this was the thing she missed most: the sense of belonging recognition bestows, and her spot near the south door.

* * *

—

The heavens no longer cracked open with thunder that made her bury her head in her shawl and call on all the saints for mercy. The last hailstorm shredded the collards and left hard white drifts under the eucalyptus trees, but that was a few weeks ago. Now rainbows vaulted through the mountains and she taught her children to sing, ‘Mary’s sash is for me, for me, Mary’s sash is for me.’ Bullroarers echoed across the fields and from behind the house came the arrhythmic chop of wood being split.

Her storerooms filled. Broad beans and peas from the market. Lentils, chickpeas, the first barley harvest. Garlic, shallots, ginger. Bags of long hot chilli peppers. It took a full day just to cut them up and spread them out in the sun to dry. The yard began to disappear under squares of green and yellow and red.

Then it was the turn of the spices. Dirty gold rhomboids of fenugreek, dry-roasted to deepen colour and flavour. Bishop’s weed, unassuming yet pungent; striated spheres of coriander seed. Angular black cumin, love-in-a-mist. Basil both sweet and sacred. Beautiful mustard seed, tiny rolling orbs of grey and umber and brown. Rue seed from the bushes that grew about her front door. False cardamom splitting under her hands to reveal dark kernels huddled into pale white nests.

When the peppers had dried to a deep blood-red and been pounded into flakes, when the chickpeas had been husked and dried and split, she began to compose the things that would inform much of what she would cook: berberé, aromatic chilli powder; and shirro, spiced chickpea flour. Ample amounts had to be provided, of course, and more than ample, but she knew that along with volume, the subtle tastes of these things in particular would be a way for hundreds of people, the most powerful in the province among them, to judge both her and her husband, the richness and status of their house. She knew that because her husband was not from Gondar it was not enough to be equal, that their hospitality must be outstanding. But she also knew she was now good at these particular arts, and that she had come to enjoy the hours she spent adding a touch of cumin here, a handful of crushed ginger there, a pinch of salt or a dusting of rue. Finally the berberé and shirro went out

into the sun again to dry.

And then the sound of grinding, of stone against spice against stone, filled the days.

* * *

—

There were still unexpected guests at mealtimes. She had kept the habit of watching out for her husband from the window, so by the time he and his guests had crossed the threshold the low stools would be arranged around the mesob and the sauce she had made that morning would be bubbling up. Servants would appear, bow, pour water for the washing of hands and dusty feet; the injera would arrive, the slim-necked flasks of mead.

She would ensure everyone was served, making the ritualised fuss, working through the catechism of offer and refusal – eat, you must eat, upon my death you must eat – that in this region preceded any breaking of bread, regardless of how hungry anyone might be, until they finally acceded that yes, they might taste just a little, just a tiny bit, just for her. She would hover, provide the generous portions that would in fact be consumed, accept a couple of mouthfuls put together for her by her husband, but she would never sit down.

As their stomachs filled and the mead warmed their veins, official business would shade into gossip. Who was looking for promotion and hadn’t a chance. Who had been seen eyeing up whose wife. Who had come out with a surprisingly sophisticated qiné. Those from Ba’ata, especially, returning with pride to their alumnus Aleqa Gebrè-hanna, whose puns and jokes had attained the status of folklore and were known by every schoolchild in the land. Did you hear the one about when he came back to Gondar, and ran out of money? He was out of favour with the emperor at the time so he sent his wife to the capital to tell Menelik he had died. Menelik, feeling guilty, sent her back with a purse full of thalers for the memorial service, and was understandably annoyed when, some months later, Aleqa Gebrè-hanna reappeared in Addis, alive and well. ‘Your majesty, they had so many rules up there,’ said Aleqa Gebrè-hanna, pointing to the heavens, ‘I preferred to return and live under yours.’ Billows of laughter would break through the house.

Then again, said one – a glance askance at her husband – our current aleqa isn’t too shabby either. Remember when he met that other aleqa in the roadway, who asked, ‘What are you doing, so far out of your way, and so late into the evening?’ She tensed. No one but evil spirits roamed at night, and Gojjamés were often accused of being evil spirits; the slur on her husband was clear to everyone. ‘And Aleqa Tsega replied, “Looking for a donkey”’ – for evil spirits attacked those who resembled donkeys. She watched as they laughed, too uproariously, flattering their host and his sharp wit, seeming to give him the spoils of victory. She saw how her husband’s answering smile did not touch his eyes.

And she remembered the old Gojjamé woman who had lived in a little room next to their compound. Her children were grown and gone, and she was destitute, so they had not been charging her rent. When she died Aleqa Tsega had wanted to give his countrywoman a respectful farewell, so they had laid down carpets from the church on the floor, beautiful Turkish carpets, and asked all the neighbours to the wake, and the churchmen for absolution. But because she was poor, and from Gojjam, no one had come.

Her husband had surveyed the empty room and said, Will this happen when I die? She had tried to reassure him, but she too had been shocked by the nakedness of the rejection, and knew she did not convince. She was not surprised when, a short while later, he began to have regular meetings with three other Gojjamé men, in which they decided to pool practical resources, to exchange information, to donate money to a fund that would provide loans to any Gojjamé person in adversity, and would be held in trust for their funerals.

* * *

—

Now the young boy cousins began to arrive, and the farmer relatives, walking in from Dembiya, from Gonderoch Mariam, from the archipelagos of hamlets in between, each with a staff slung across his shoulders, and on the staffs heavy hide sacks. When she reached into one and drew out a piece of honeycomb she saw some bees had not escaped the smoke and were curled, still, in their cells. She felt sorry for them, deprived of their holy handiwork and of their families, and hoped they’d had a quick death. With a finger she caught the dripping honey and brought it up to her mouth. It tasted of sunshine, of breezes scudding across mountain meadows.

The buckthorn was nearly ready. The bushes in their compound had been stripped of their leaves, and more had been bought in the market. For a few days now they had been spread out in the yard, drying.

Weeks ago she had sowed a patch behind the house with pumpkin seeds, then had gone out each morning to check on seedlings, to lift widening leaves and peer at the fruits growing underneath. She would bid them good morning, ask how they spent the night, had seen so many develop that standing among the searching tendrils, counting them, she had laughed to herself in amazed delight. But now they had been harvested, the soft watery flesh cut into cubes that lay in the sun, shrinking and sweetening.

* * *

—

When Alemitu turned seventeen Aleqa Tsega chose a student of his, a clever one who could read and write, and told his eldest daughter this would be her future.

One of Yetemegnu’s half-brother’s daughters was marrying too, so they threw a huge party. The food was rich, abundant – whole sides of oxen, perfectly seasoned chicken sauces, all the parts of many sheep, each dish ringing all the available notes of flavour and texture and skill. The das stayed up for days, the music rarely ceased, the women danced. The men took it in turns to declaim couplets they composed on the spot, about the mead, the food, the bride. Yetemegnu stood, and went to join the dancers, the half-sisters, cousins, nieces, the neighbours and the neighbours’ daughters, and they welcomed her in.

It was a slackening in their attention she felt first, a stumble in their support, and a dropping of their gaze. She turned to her husband. His face was closed tight, his eyes small. Anger flared in her at this again. I thought we were finished with this. Look, our first daughter is married, silent as custom requires, there under her muslins. Surely it is right, necessary even, that I should take this lead?

Then she heard the laughter. She looked around. One of the men, a relative from Infiraz, stared back bold and straight. Pleased with himself, he repeated his verse:

You have a horse and a mule stabled in your byre.

Why go looking for any other animal?

* * *

—

There were gans everywhere. Stacked up under trees, ranged along the outside wall of the kitchen, a squat pottery army, awaiting orders. All day now a fire burned, and one by one the gans, their insides washed in ironweed and soapwort, were rolled over and suspended above the fire. They swayed, gently, drinking up borage smoke and sweet wild olive.

The storerooms were overflowing. Green and black chickpeas, white broad beans, hard yellow split peas, maize. Wheat and barley and sorghum. Finger millet. Shallots and garlic and ginger and coffee. Limes she picked up and held to her nose, taking breaths so deep they made her dizzy: the advent fast had begun, and no one ate till past midday. She tracked household expenses only, but she knew these intoxicating smells and colours represented a large proportion of a year’s income, much, in fact, of what wasn’t being spent on his church. The responsibility tightened her shoulders, hurried her steps, began to enter her dreams.

She ground the buckthorn to powder, mixed it in water. She soaked the maize so it would sprout, and the millet. Then she turned her attention to the mead. This was the more precious drink, intended, until recently, only for aristocracy, but it was simpler to make: just water and honey for the moment, three parts water to one part honey, stirred and covered and left to ferment. She took extra care these days though – she remembered how, a couple of years ago, Ras Ayalew had called her husband over in the middle of the party and pointed out that the beer was mellower than the mead. Her husband had bowed and smiled and made admiring comments about the ras’s refined palate, but later had shouted at her in embarrassment and demanded it never happen again.

> When three or four days were up – she could tell, from the smell, when it was time – she went looking for a relative tall enough to reach the hardened cakes of barley sprouts, now perfectly smoke-touched, down from the rafters. She pounded some into pieces, then added them to the beer barrels along with a crumbled pancake of wheat and finger millet, the germinated (and now dried and pounded) maize, and a little more ground buckthorn, sprinkled on top and swirled with a stick into the darkening mixture. A handful of fine-ground buckthorn went in with the honey, too, and more water, and both were covered again. Within a few days the smells of beer and mead rose, mingling and drifting throughout the rooms.

* * *

—

In her ninth pregnancy she spent much of her time spinning. She was a grand lady now: her husband was comfortably established, or seemed to be, she was in her early thirties, she had servants and growing children who helped with the work – those who were not in school, at least. Her husband, seeing on his trips to the capital how the emperor favoured modern schooling, how increasingly he sent the brightest abroad to study, then brought them back and appointed them to the highest posts, had taken his sons out of the churchyards and enrolled them in modern elementary school. So now she could more often do what was expected of women of her station: sit on a daybed, and direct operations. From the basket at her side she took a cloud of cotton, thinned where the dark seed had been picked out, and snared it with the hook on her spinning reed. A quick twist of her right hand, and the cloud shrank toward a point. Her left hand steadied the cloud, let it out gently. Another twist, and another, until her right arm was stretched out straight and between her hands quivered a white thread, tiny fibres along its length escaping and catching the light. She wound it tight around the top of the reed, picked up another cloud of cotton, and began again. Eventually there would be enough for a winter blanket.

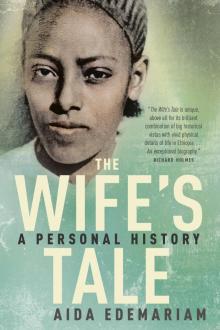

The Wife's Tale

The Wife's Tale